There’s an old saying: “God writes lousy drama.” It’s very familiar to anyone who writes historical fiction in any capacity, and even if you’re an atheist, it’s still apt. The idea is that you can’t write most stories exactly as they occurred (to the extent documented, that is) because even riveting history can make for a dull book or play. Writers can derive a lot of comfort from this saying, because it offers a certain amount of carte blanche to alter history as needed to suit a narrative. Of course, you can also run into trouble if you start thinking it lets you off the hook when it comes to complicated history and research.

I happen to love research (most of the time) and am proud of my history geekdom. Whatever I’m writing, I tend to prefer historical settings because the past can illuminate so much about the present—and about ourselves. I also like the clothes. So whether I’m writing something serious or funny, fantasy or no, I tend to dive into the past. Additionally, not to sound like a vampire myself, it also gives me no end of subject matter to pilfer. I have a ridiculously good time taking history and playing with it—all respect and apologies to my former professors, of course.

As much as I love the hard work of the research, when I begin a new project, it’s very much the characters’ stories that come first. My main service is to them and their journey. If I don’t tell their truth, it doesn’t matter how historically accurate or interesting I am—the story won’t feel true. (Or keep anyone awake.) So in the early days of crafting a piece, I concentrate on the characters and their emotional arc.

After that, the history and emotions run neck and neck because the dirty secret is that there is absolutely no way I could pretend to tell a true story about a character in a given period if I did not know the true history. Or rather, I could pretend, but everyone reading it would see right through me and would—rightly—flay me for it. So you could say the research both helps me get at the truth and keeps me honest.

It’s usually at this point in the process that I begin to get contradictory. I feel it incumbent upon myself to be historically accurate (getting two degrees in the field will do that to you) but I also don’t like to be slavish to exactness. Going back to the point about God writing lousy drama, it just doesn’t serve anyone to let the history overtake the narrative. So it becomes a balancing act. That is, I try to stay as absolutely accurate as possible, but don’t lose sight of what’s really important. Every now and again I have to remind myself—this is not a thesis, it’s fiction.

Which is much easier to remember when it’s vampires in the midst of World War II. In this instance, I’m definitely reinventing and playing with history—and enjoying every minute—but I often feel as though the onus to be accurate in every other aspect of the work is that much heavier. Fiction it may be, but I want it to feel real both for myself and my readers.

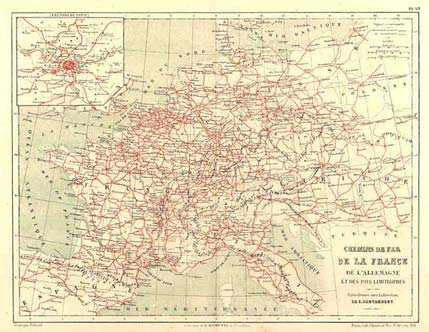

One thing I have found in the research process is how it can really bog you down if you’re not careful. One of The Midnight Guardian’s three narratives follows a train journey from Berlin to Bilbao and I spent ages trying to find the exact route, including stops and schedules. At some point—it may have been when a librarian was throttling me, I don’t remember—I realized that I was tying myself up in a knot trying to find details that ultimately didn’t further the narrative. I wanted to have all that information, but having it would not have improved the story. So I did something that is not always easy for me and let it go.

I think letting things go can be difficult for a lot of writers of historical fiction. There are two problems—what you don’t find, and what you do. When I was buried in books, maps, and papers studying Berlin and the war from 1938-1940, I found any number of details and stories that I thought would be fun to weave into my characters’ narratives. I even wrote quite a few of them. But as I was refining the manuscript, I came to the hard realization that, cool though a story might be, it didn’t necessarily work with my characters and so out it went. It was one of the hardest things I had to do—but the nice thing about writing is that no one sees you cry. Besides, when the story ends up better, there’s nothing to cry about anyway.

Sarah Jane Stratford is a novelist and playwright. You can read more about her on her site and follow her on Twitter.